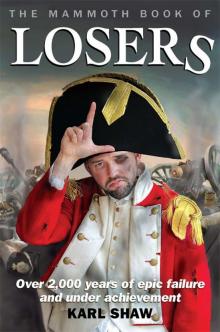

The Mammoth Book of Losers Read online

Page 10

Historia Naturalis was so influential that by the time anyone got around to seriously challenging his teachings, Pliny the Elder had been dead for over a thousand years, having discovered during the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79 that there was no cure for standing next to a volcano to get a better look.

“I cannot conceive of any vital disaster happening to this vessel. Modern ship building has gone beyond that.”

Edward J. Smith, captain of the RMS Titanic, 1912

Least Accurate Attempt to Date the Earth

In the summer of 1650, an Irish priest from Armagh, James Ussher, published a monumental book called The Annals of the Old Testament. The project, which occupied 2,000 pages in Latin, was a formidable piece of academic research that took up twenty years of Ussher’s life and caused him to go half-blind in the process, but the most important piece of information in the whole book appeared in the very first paragraph of the very first page.

By adding together the life spans of all the descendants of Adam, Ussher worked out that God created the Earth on the evening of Saturday, 22 October 4004 BC – at nightfall, around 6p.m., if you want to be more precise. What happened before that, at 5.30 p.m. for example, Ussher didn’t say, or rather couldn’t. According to Christian doctrine, before 6p.m. on 22 October 4004 BC, time itself did not exist. God did nothing all.

Ussher was congratulated by almost everyone for his stunning piece of historical scholarship. It confirmed something Christians had assumed to be correct for centuries: that the world and mankind were as old as each other – that is, not very old at all. In 1675, a London bookseller called Thomas Guy started publishing Bibles with Ussher’s date printed in the margin of the work. It was a great bit of business and Guy’s Bible became immensely popular, although this might have had more to do with his engravings of bare-breasted biblical women than the inclusion of Ussher’s chronology. A few years later, the Church of England also began printing Ussher’s date in its official Bible and, before long, the date was appearing in Bibles so often that it was practically accepted as the word of God.

Of course, there was the odd sceptic, and not just about Ussher’s dating system. A Frenchman called Isaac La Peyrère politely pointed to some discrepancies in the Old Testament itself. If there were no other people in the world before Adam and Eve, where did their son Cain find himself a wife? And why did God have to mark Cain so that people knew who he was? Surely, if the only people around were Cain’s parents and his sibling, they would know who he was anyway?

When La Peyrère wrote up his concerns in a book called Men Before Adam, he was hauled before the Pope and forced to apologize. Long afterwards and at a safe distance from the Vatican, La Peyrère insisted that, actually, he had only mumbled his apology and had not, in fact, retracted a single word, and for the rest of his life he was quietly convinced that the book of Genesis had got it all wrong.

La Peyrère was very lucky. The Catholic establishment was not known for being reasonable with people who entertained doubts about the literal accuracy of the Bible. In 1600, Giordano Bruno was burned to death for questioning Christ’s divinity and suggesting that the universe was infinite. The Inquisition cut out the tongue, strangled, then burned a doctor called Giulio Vanini who suggested that there might be a logical explanation for the biblical miracles. Little wonder then that Ussher’s date for the age of the Earth continued to hold sway, largely unchallenged, for the next 200 years or so. In fact, it was still being printed in the margin of Bibles right into the twentieth century.

La Peyrère’s hypothesis, however, had opened people’s minds to the possibility that the Earth might just be longer in the tooth than the Church said it was. In 1770, the French scientist Jean-Baptiste-Claude Delisle de Sales challenged the age given by Ussher. He claimed that, based on astronomical data, the Earth was around 140,000 years old and had taken at least 40,000 years to cool down since its formation. For his pains, de Sales was jailed and most of his books were burned.

In the 1860s, Ussher’s date was once again challenged by science; in particular, a cheeky new arrival called geology suggested that the Earth was at the very least twenty million years old.1 Thanks to radiometric age dating, we know now that the Earth is about 4.55 billion years old. So Ussher was only out by 454,994,346 years . . . give or take.

“Hard Luck” Scheele

Despite having had no formal scientific education, the eighteenth-century Swedish pharmacist Carl Wilhelm Scheele made remarkable contributions to chemistry.

He discovered oxygen three years before Joseph Priestley, but didn’t get around to publishing his findings until 1777, by which time Priestley had already taken all the credit. He went on to discover several more elements – such as barium, chlorine, manganese, molybdenum and tungsten – as well as compounds including citric acid, lactic acid, glycerol and hydrogen cyanide. He also discovered a process similar to pasteurization and a means of mass-producing phosphorus, which led Sweden to become one of the world’s leading producers of matches. But in every case, someone else took the credit.

Scheele might have gone on making great discoveries if it hadn’t been for his habit of sniffing and tasting every chemical he worked with, including such lethal substances as mercury and hydrocyanic acid – a chemical so deadly that even inhalation or contact with the skin could lead to a horrific, painful death. Any one of these could have accounted for his sudden and premature death at his laboratory workbench at the age of forty-three.

“Beef cattle the size of dogs will be grazed in the average man’s backyard, eating specially thick grass and producing specially tender steaks.”

Science Digest article “Your Life in 1985”, 1955

Most Accident-Prone Astronomer

The history of proper astronomical research began with a Dane called Tycho Brahe. Before Brahe, astronomers made the odd observation of their own, then added their findings to whatever else had been handed down to them from the great stargazers of antiquity. Brahe was the first person to see that a proper understanding of the movements of the planets required a long series of painstaking observations of their motions relative to the fixed stars. But Brahe is remembered today not so much for his brilliant scientific career as for being prone to bizarre mishaps.

He was born in 1546 to a noble Danish family in Knudstrup, now in Sweden but then part of Denmark. His father Otto served the King of Denmark as Privy Counsellor. Brahe was groomed for a career in law, but wanted to become an astronomer, very much against his family’s wishes, after witnessing a partial eclipse of the Sun when he was a teenager. His big break, however, came not as an astronomer, but as an astrologer.

On 28 October 1566, there was an eclipse of the Moon and, on the basis of a horoscope he had cast, Brahe announced that the eclipse foretold the death of the Ottoman Sultan, Sulemain “the Magnificent”. At the time, it was not difficult with a little imagination to read astrological significance into just about anything observable in the sky; the religious wars of the Reformation were in full swing and Europe was in turmoil. Brahe’s prediction, however, was very popular because Sulemain, as a Muslim, was hated by Catholics and Protestants alike. When news broke that the Sultan had indeed expired, Brahe’s reputation as a man of learning was sealed. Some of the gloss was taken off the prediction by the fact that Sulemain was already eighty years old and it later emerged that he had, in fact, been dead for several weeks before the eclipse, but no one seems to have made too much of it. Brahe was now internationally famous and able to hob-nob with the crowned heads of Europe. One of his biggest fans was King James VI of Scotland, the future King James I of England.

Brahe was planning to move to Basel in Switzerland where he could be closer to the southern European centres of culture, but in 1576 the Danish King Frederick II, basking in the reflected glory of his new home-grown hero and desperate not to lose him permanently, made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. Frederick gifted his celebrity astronomer the island of Hveen, along with substantial treasury funds, t

o set up a permanent observatory.

Brahe set about constructing a fantastic castle observatory, which he called Uraniborg, equipped with a range of instruments of remarkable size and precision, the like of which the world had never seen. It cost the equivalent of 30 per cent of the annual revenues of the Danish crown, about $5 billion in today’s currency, but in scientific terms it was money well spent. Although he didn’t even have the benefit of a telescope, armed with his naked eye and a quadrant Brahe made a vast number of astonishingly accurate astronomical measurements, including a comprehensive study of the solar system, pinpointing the positions of hundreds of stars.

As well as his scientific duties, he was also obliged to provide annual astrological predictions for the royal court, although by now Brahe wasn’t entirely convinced of its usefulness. This didn’t stop him from drawing up a list of days in the year called “Tycho Days” when it was considered advantageous to stay in bed, because unfortunate events were bound to occur. Even today in parts of Scandinavia, a day when everything goes wrong is called a “Tycho Day”.

Brahe’s future seemed secure, but not everyone was enamoured of the King’s favourite. In between mapping the skies, the astronomer ruled his island kingdom in a grand style and with a thoroughly autocratic hand. It was home to a huge retinue of servants and scientific assistants and, as well as his observatory, he built a chemical laboratory, a paper mill, a printing press and a dungeon for imprisoning recalcitrant tenants.

The Danish astronomer royal was not the sort of man you would want to get into an argument with. Arrogant and hot-tempered, he fought duels, scandalously kept a mistress who bore him eight children, employed a dwarf as a jester, dabbled in alchemy and generally tyrannized the local peasantry. Then there was some unfortunate business concerning Brahe’s pet elk, which apparently got drunk during the night, fell down some stairs, broke a leg and had to be shot. What it was doing upstairs drunk in the first place is of course nobody’s business but Brahe’s.

There was something else that set Brahe apart. As a twenty-year-old student at Rostock, he got into a quarrel at a party with fellow academic Manderup Parsbjerg over who was the better mathematician. They decided to take it outside in the form of a duel, conducted in pitch darkness, with rapiers. Brahe escaped with his life but not his nose. He concealed the loss of face as best he could with an artificial bridge made of gold, silver and copper. He carried a small pot of glue with him at all times to keep his precious metal proboscis firmly in place.

Brahe’s bad behaviour was tolerated so long as his friend King Frederick was alive. His son King Christian, however, was less forgiving of the high-maintenance celebrity astronomer and promptly cut off Brahe’s pension. Brahe left Denmark in a huff and went to Prague seeking employment with the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II. He and Brahe got along famously: the Emperor had a number of odd interests, including a pet tiger, and was thought to be insane. Brahe was appointed Imperial Mathematician, although the job description also required him to keep the Emperor up to speed on any other general insights he had about the mysteries of the universe and he was also expected to cast the odd horoscope.

It was probably drink that did for Brahe in the end. In October 1601, he was invited to a banquet at the Prague palace of the nobleman Peter Vok Ursinus Rozmberk. He enjoyed the copious amount of food and drink on offer but, being a nobleman and well versed in table manners, etiquette prevented him from leaving his seat to empty his full bladder before his host left. By the time he got home, his bladder had swollen so much that he was unable to sleep or urinate. Intestinal fever and delirium followed and he died in agony eleven days later. His final words were: “Let me not seem to have lived in vain.”

For many years, it was assumed that Brahe had died either from uremia, or from a burst bladder, but the unusual circumstances of his death has since led to suspicions that it was not accidental. Brahe employed an assistant, Jahannes Keppler. The two did not enjoy a particularly amicable working relationship because Brahe always jealously guarded his astronomical data and didn’t allow Keppler to see it. Brahe’s children were not acknowledged as his legitimate heirs and, when he died, there was a great deal of confusion as to who was in line to inherit his research. Keppler took advantage of the situation and stole the data, using it to further his own research into the underlying laws that govern the orbits of planets. On the back of Brahe’s data, Keppler became much more famous than his luckless former employer.

A forensic analysis of Brahe’s hair in 1991 showed a sudden spike in the amount of mercury in his body shortly before his death, leading many to believe that he had been poisoned by Keppler. Perhaps Brahe’s final misfortune was to have been killed in the name of science by an ambitious rival.

Least Successful Horoscope

The sixteenth-century Italian polymath Girolamo Cardano wrote on a wide variety of subjects including medicine, astronomy and philosophy. His addiction to gambling led to his pioneering studies of probability and chance. His reputation as a mathematician was so great that he was consulted by Leonardo da Vinci on questions of geometry.

As a sideline, Cardano also earned international fame as the most successful astrologer of his day and he was hired to cast horoscopes for the crowned heads of Europe, including England’s young King Edward Vl. He once cast a horoscope for Jesus Christ and was briefly imprisoned for blasphemy. He even predicted his own death, down to the very hour, at the age of seventy-five. When the time arrived (21 September 1576) and Cardano found himself in robust good health, he committed suicide rather than admit he was wrong.

“Housewives in fifty years may wash dirty dishes right down the drain. Cheap plastic will melt in hot water.”

Popular Mechanics, 1950

Least Comprehensible Scientific Paper

The idea that the world has existed for a very long time indeed – or, at least, much longer than the Bible claimed it did – came from a Scot called James Hutton. Born in the Scottish borders in 1726, Hutton trained as a doctor and enjoyed a successful career as a chemist, then retired in his early forties to become a farmer. He was also a member of the Oyster Club in Edinburgh, a posh talking shop where enlightened men of independent means – lawyers, writers, philosophers, doctors and artists – could share ideas over claret, salt haddock and oysters. Membership included the economist Adam Smith, the philosopher David Hume and the chemist Joseph Black. Hutton took an interest in everything from canal building and heredity to fossil collecting, but his chief interest was in rock formations.

It occurred to Hutton that by tracing back the origin of the various rocks and minerals on his farm, he might arrive at some clear understanding of the history of the Earth. He spent over thirty years of travel and field observation building up a vast knowledge of rocks and their distribution throughout the British Isles. One thing that baffled Hutton, something that had puzzled people for ages, was that shells and other marine fossils could be found on top of mountains. Some people thought they had the answer: they had been deposited by mighty floods – the biblical Flood, perhaps. Hutton had another idea; what if the fossils had risen along with the mountains themselves?

Hutton gave his theory its first public airing in 1785 in front of the new Royal Society of Edinburgh. He said that the planet was in a state of continuous change. Continents were being eroded and renewed by processes at work at that time, had always been at work and would be repeated in the future. Soil was washed down to the sea, formed into rock and then uplifted under the tremendous force of subterranean heat. These cycles of decay and renewal occurred in indefinite time, “so that, with respect to human observation, this world has neither a beginning nor an end”. Hutton’s insight was simply quite brilliant – it opened the door for scientific theories from the biological evolution of Darwin to atomic theory and the Big Bang.

Unfortunately, hardly anyone at all took any notice. For all of his intellectual brilliance, a gifted communicator James Hutton was not. He was incapable of writing plain Engli

sh even if his life depended upon it. When he got around to publishing his theory, it ran to two volumes and nearly a thousand pages of the most unreadable prose ever written. It was a rambling, grammar-free mess, crammed with the sort of jargon that even fellow geologists found impossible to follow. And that was the easy bit. Half of the book consisted of quotations from French sources, still in the original French. In a very crowded canon, it was the mother of unreadable scientific books. Even the experts thought that life was too short to spend reading Hutton’s book about time.

And so it was that that Hutton very nearly became, at best, a footnote in the history of geological discovery. Fortunately, however, there was someone who had not only taken the trouble to read Hutton’s book, but could actually understand all of it – his friend John Playfair, who was a professor of mathematics at Edinburgh University. Five years after Hutton’s death in 1802, Playfair published a heavily edited version of Hutton’s principles, called Illustrations of the Huttonian Theory of the Earth. For anyone who took an interest in geology, it was revelatory.

But buried somewhere in his original, unfathomable 2,000-page manuscript was an even more extraordinary insight. Hutton had also written a chapter on the origin of species, in which he noted:

If an organized body is not in the situation and circumstances best adapted to its sustenance and propagation, then, in conceiving an indefinite variety among the individuals of that species, we must be assured, that, on the one hand, those which depart most from the best adapted constitution, will be most liable to perish, while, on the other hand, those organized bodies, which most approach to the best constitution for the present circumstances, will be best adapted to continue, in preserving themselves and multiplying the individuals of their race.

The Mammoth Book of Losers

The Mammoth Book of Losers